Tribal nations, including the Catawba Indian Nation, begin to feel the effects of recent eliminations of federal grants and layoffs, impacting areas such as food security and health services.

As President Trump nears his hundredth day in office, federal agencies and employees are making sense of the expansive workforce cuts and proposals to freeze federal funding the administration threatened as part of its initiative to shrink the size of the federal bureaucracy. While not the focus of these cuts, Native programs and grants are highly dependent on federal funding and likely to suffer the impacts of a variety of the Trump administration’s fiscal decisions.

According to the Associated Press, President Trump and Elon Musk intend to eliminate over 25 percent of jobs at the Bureau of Indian Affairs, which handles the allocation of critical resources and funding for tribal nations. Multiple representatives of indigenous communities told the press that they felt these cuts were uninformed and illogical, as the majority of federal funding to tribes consists of less than 1% of the federal budget and provides needed services, not the maintenance of “inefficient” bureaucratic red tape.

Nonetheless, layoffs have been announced by the Trump administration in the Indian Health Service, the Department of the Interior, the Bureau of Indian Affairs and the Bureau of Indian Education, according to Minnesota Public Radio.

In a written statement from John Echohawk, Executive Director of the Native American Rights Fund, he wrote, “Tribal Nations rely on federal funding to address essential needs, including public safety, healthcare, education, infrastructure, and the basic needs of our most vulnerable citizens.”

Echohawk criticized the administration’s widespread attempts to freeze federal funding, noting the likelihood that these will disproportionately affect the Native communities his organization advocates for.

Due to the unique arrangement of tribal governments, federal funding and grants must be used to support basic services which local and state taxes would typically cover in other areas. This includes the salaries of nurses, police officers, professors at tribal colleges and firefighters.

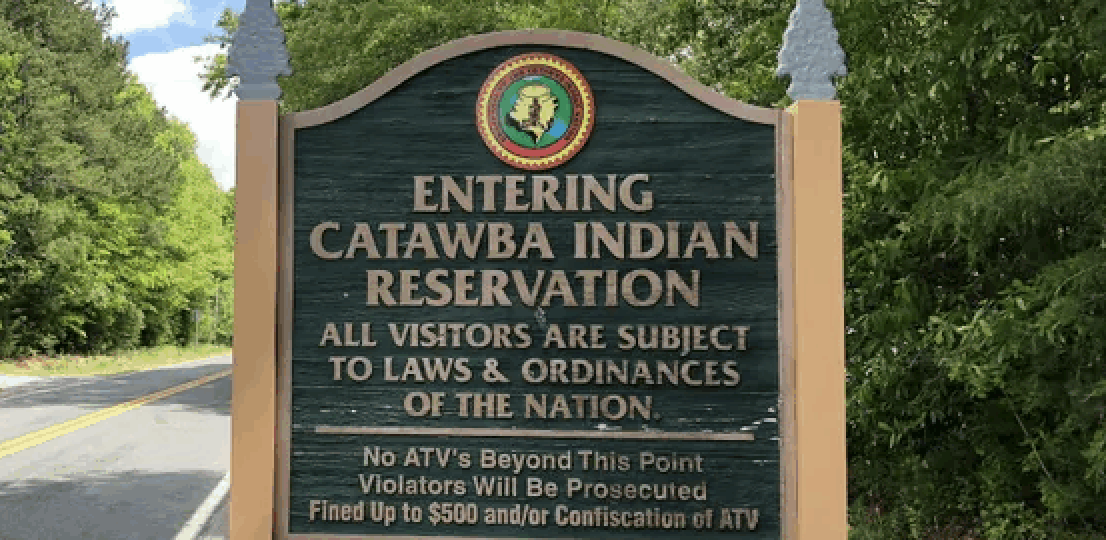

The Catawba Indian Nation, about ten miles east of Winthrop, is not exempt from the recent elimination of federal grants.

Tylee Tracer-Anderson, Chief of Government Affairs at the Nation, shared how the Trump administration’s cuts to the USDA have recently impacted their Local Food Purchase Assistance (LFPA) grant.

“We used grant monies to buy produce from local farmers and ‘sell’ it back to tribal members. Tribal members would sign up for the program and they would be given vouchers they could exchange for the food. We call it the Black Snake Farm Farmer’s Market. Many of our citizens have food insecurities and this program helped combat some of that,” Tracer-Anderson said.

Now that they no longer have access to the grant, the stability of this poverty-reducing program is uncertain.

The Catawba Indian Nation receives a variety of federal grants and funds, with usaspending.gov putting the number at $16.9 million and TAGGS (Tracking Accountability in Government Grants System) reporting $10.7 million in spending for 2024. These address a wide range of tribal issues, including Health and Resiliency Projects, Tribal Opioid Response, Family and Youth Services and domestic violence shelters.

Other specific instances of funding cuts directly affecting tribal nations include the removal of scholarship grants and the jeopardizing of health services.

Since 1994, tribal colleges have received support from the federal government as “land grant” universities, part of the Equity in Educational Land-Grant Status Act carried out by the USDA. In March, ProPublica reported that “at least $7 million in USDA grants to tribal colleges and universities have been suspended.”

These educational institutions are incredibly dependent on such grants, as they often have low endowment funds and support from the community. The recent cuts have led to halting of needed maintenance and construction projects, freezing of professor’s salaries and insecurity around student scholarships, causing some to doubt their ability to remain students for the rest of the semester.

Some university representatives question whether their schools are specifically being targeted compared to non-tribal colleges and universities due to the 1994 act’s use of the word “equity.” This act, although part of a fulfillment of government responsibilities to provide “basic funding” for education, may have been implicated in the slashing of all programs mentioning diversity, equity, inclusion or DEI.

This concern about appearing too progressive or race-centered in their assistive policy has been recognized by those who fear ill-informed cuts to necessary programs. “Native leaders are pushing Trump officials to acknowledge that the feds’ relationship with tribes is based on their status as sovereign nations, not racial preference,” Stateline reported.

Another area of particular concern is the Indian Health Service, which laid off 950 employees in Feb. – although Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. soon rescinded the action.

IHS is responsible for running tribal clinics and organizations, supplementing the salaries of nurses and practitioners, and supporting plans to build needed medical facilities. These resources are already reported to be highly underfunded, so any threat to freeze federal grants puts the health and wellness of native communities in a precarious position.

While many of DOGE’s initiatives have been questioned for their legality, native issues are especially contentious. The federal funding tribal nations receive are bound by a variety of historical native treaties and trusts that establish the United States as responsible for sustaining basic resources such as infrastructure, education, law enforcement and healthcare.

Director Echohawk reiterated that the United States has a duty to protect native land, resources, and people, saying, “To withhold our money from us without reason or warning is illegal and immoral.”

The federal government is obligated to maintain this funding as part of its “trust responsibility” promise which extends outside of congressional decisions as a part of basic Indian law. Along with this is a requirement to consult Native governments before making any adjustments to funding that will affect the community, making the administration’s actions illegal, as noted by the Associated Press.

The Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act 1975 additionally provides native communities greater autonomy over federal funding, allowing them to allocate and move federal money where they see fit. This enables tribal nations to take control over federal programs and continue to receive funding through reimbursement, which some tribes have recently reported holdups in accessing.

Those who do not utilize the act but instead receive “direct funding” are at a greater risk for losing basic services due to federal layoff and budget reductions.

Today, tribal communities feel left in the dark about the future of their relationship with the federal government. A lack of communication with federal agencies such as the EPA, little warnings prior to grant eliminations and minor details as to the reasoning and timeline of grants has created great uncertainty for these communities.

As an already underfunded and under-resourced group, tribal nations’ reliance on the federal support they do traditionally receive places them in a vulnerable position to any attempts to reduce government spending. In opposition of centuries old treaties and promises made to native communities, the Trump administration is likely to face legal challenges as its efforts continue.