Animation studios of the past and present like Studio Ghibli or Pixar have defined the mainstream animation industry for years, but Irish animation studio Cartoon Saloon has made a name for themselves as of recent.

With their first feature film, “The Secret of Kells,” the founder of Cartoon Saloon, Tomm Moore, established his talent as a first-time director. The authentic hand-drawn animation caught the attention of film critics and even the Academy Awards, where the film got a nomination for Best Animated Feature.

Moore’s sophomore feature “Song of the Sea” gained more traction for the studio and Moore, earning a second Academy Awards nomination for the studio. Moore then moved to work on a new project as co-founder Nora Twomey directed and produced the critically acclaimed film “The Breadwinner,” which again earned the studio an Academy nomination.

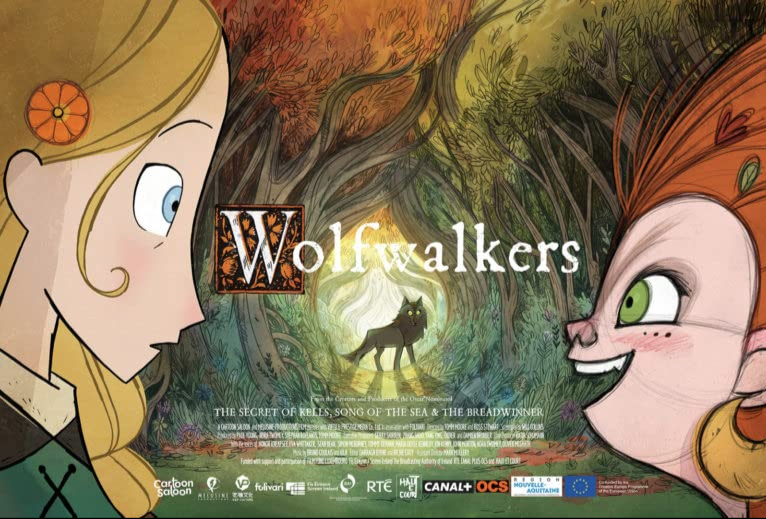

Over the past few years, Moore has been working hard on his newest project, titled “Wolfwalkers,” and the effort paid off.

“Wolfwalkers” is a beautiful return for Moore, and surprisingly a step-up from his previous works.

The film focuses on Robyn, the daughter of an esteemed wolf hunter, who finds herself becoming friends with a Wolfwalker, a human that transforms into a wolf when she sleeps. Because of the institutionalized hatred towards wolves employed by a totalitarian regime, Robyn sets out to save the Wolfwalker and the wolves from an impending attack.

The themes align with any other children’s film, tackling the concept of the ‘other’ and how people should accept everyone no matter their differences. However, the execution of both the filmmaking and the screenplay allows this trope- heavy narrative to succeed.

Moore has always derived most of his art style from Irish folklore and historical paintings from all over the world. The two aesthetics he chose for “Wolfwalkers” were Japanese woodblock prints and loose, expressive linework. Japanese

woodblock prints were popularized in the Edo period of Japan, running from 1603 all the way to 1868.

This style was utilized in the art of the main town, which is drawn similarly to how it would look on a map. By contrasting the flat, almost boring nature of the town with the more exciting and natural aesthetics of the forest through the artwork, the forest can be fully appreciated in its beauty. The expansive ecosystem of the forest is entrenched in Celtic art and folklore, creating an immersive environment.

Even the character designs mark this contrast as the town’s citizens are drawn with exact linework.

Lord Protector Cromwell exemplifies this aesthetic with a rectangular body and head.

The loose linework aesthetic is applied to the Wolfwalkers, the wolves and even Robyn as she comes closer to nature. Rather than utilizing exposition to establish the divide between the forest and the town, the artwork inherently distinguishes their differences.

The dynamic nature of the cinematography was an interesting addition to the already incredible technical design of the film. While the presence of a camera is impossible with animation, momentum can be used to convey similar emotions

of a well-shot live-action film. When a Wolfwalker becomes a wolf, the film transitions into a first-person perspective. The shift between calculated and still frames to energetic cinematography might be abrupt to viewers, but the execution of the movement is so fluid that the transition becomes seamless.

Both framing styles are beautifully hand-drawn, so none of the authenticity is lost no matter how experimental the film may get. There are also clever changes in aspect ratio to signify tonal shifts and thematic details. Through the creative and subversive visuals, any sign of contrivance is overshadowed.

Despite the fact that the plot in concept is derivative, the execution adds nuance to the thematic foundation. Discussing institutionalized hatred is nothing new for children’s movies. Movies like the most recent “Addams Family” reboot utilize the concept of “the other” in a superficial fashion, focusing on the differences between the group rather than how such hatred can manifest.

“Wolfwalkers” takes on the latter, setting the town within totalitarian rule in which wolves are demonized. To contrast the beliefs of the citizens with the audience, the very first scene depicts a Wolfwalker healing a wounded farmer outside

the walls of the town. Once Robyn becomes just as disillusioned to the demonization of wolves as the audience, she becomes the moral vehicle for the story. It still takes Robyn time to adjust to her new perspective, showcasing how deep the hatred is founded within their culture.

However, when she does fight for the wolves, the movie supports its audience to trust in not just children, but emotions themselves rather than a tyrannical force like Lord Protector Cromwell or a culture founded in illogical and imbalanced beliefs.

“Wolfwalkers” is enveloped in Celtic folklore and history, but the emotions conveyed in its art and narrative are far more universal than one would think. Cartoon Saloon continues to show how dynamic 2D animation can still be, and “Wolfwalkers” is their best exemplification of that. With wonderful animation and a nuanced narrative, “Wolfwalkers” earns a 9 out of 10.