Almost every actor has seen those burning questions on an audition form – “Are you willing to do a stage kiss?” “Are you comfortable with scenes of a sexual nature?” “Are you willing to be onstage in your underwear?” For many actors, there is an unspoken pressure to say yes to these questions, and to say yes to anything brought up in rehearsals simply because everyone is replaceable. However, the theatre, film and television industries are working to make actors feel comfortable setting boundaries and to take care of the dignity and emotions of everyone involved. Even Winthrop theatre students are finding ways to create safer, healthier love scenes by emphasizing consent, boundaries and the line between characters and colleagues.

Senior theatre education major Emily Krull remembers a difficult experience in high school, when a teacher did not treat a kissing scene with the care she and her fellow student needed. “I had to do a kissing scene for class. The assignment wasn’t kissing itself, but the one I was assigned had a kiss. I was in an abusive relationship at the time with a boy who didn’t even like me hanging out with guys, so the fact that I had a kissing scene made me anxious. We did the scene once and the professor didn’t like how we were doing the kiss and made us do it again, and again, and again,” Krull said. “[There was] no talk of boundaries, no talk of safety, no privacy to rehearse this intimate moment. The whole rest of the class watched us try to kiss 10 plus times.”

Krull says she and the other student did not feel safe or ready, and she didn’t fully understand the physical reactions her body was having. “By the end of it, I was almost crying and my professor didn’t understand why I was so bothered because ‘I’ll have to do this eventually when I’m acting in the real world’.”

In last year’s production of “At Home at the Zoo” by Edward Albee, Krull says student director Maddie Willard had a much more comfortable approach to directing the relationship between Krull’s character and her husband, played by theatre major Cameron Muccio. “Maddie had Cameron and I do a consent exercise. We didn’t kiss in the show, but the exercise taught us where each other’s boundaries were and ensured we felt safe with each other to explore our relationship as a married couple. It was doing those exercises that made me realize I could’ve done that kiss from years ago way better and felt way safer had I been taught those consent exercises and my friend and I understood each other’s boundaries.”

Many larger theatre companies are utilizing intimacy directors, an emerging field dedicated to advocating for actors’ boundaries, making intimate scenes safer and more accurate. The film and television counterpart is called an intimacy coordinator, a position that was first used in HBO’s “The Deuce” and recently in the Netflix series, “Sex Education.”

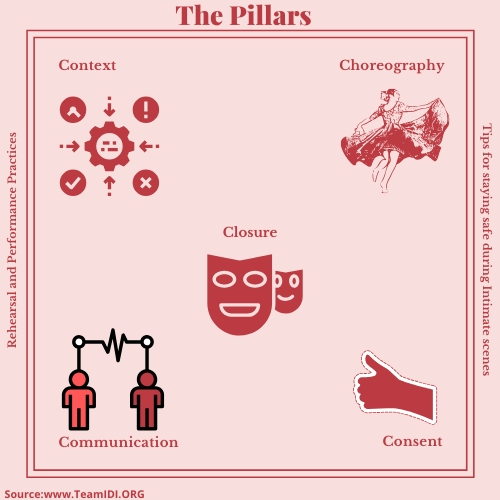

Jill Matarelli Carlson is an associate professor of theatre at East Carolina University in Greenville, North Carolina. She is also a trained fight choreographer and intimacy director through the organization Intimacy Directors International, or IDI. Matarelli Carlson says intimacy directors have a “multi-pronged role,” in that they work with actors as well as directors for a variety of purposes. “[They] work with the director to help tell the story that the script and the director want to tell, and they choreograph the action of intimacy as well,” Matarelli Carlson said. “It’s not only about keeping actors safe, but telling better, more specific stories.” Intimacy directors and coordinators can also help find better alternatives to actions that actors may not be comfortable with.

Like Krull’s former teacher, many actors have the mindset that they have to consent to intimate scenes whether they are comfortable or not. “The pressure is always on the actor to say ‘yes, I’m fine with that’ whether the answer is actually ‘yes’ or not, because they want to be cast again. They want to be thought of as good to work with,” Matarelli Carlson said.

Matarelli Carlson began as an actor, but focused more on movement in graduate school, eventually becoming a certified teacher with the Society of American Fight Directors. Matarelli Carlson says as soon as she heard about the emerging intimacy director field, she was “100 percent on board.”

“Often as a movement coach or fight director, I had been asked to do this type of thing, but without it being a title or without there really being a codified process for it,” Matarelli Carlson said. “I already had the movement vocabulary for it, and I am passionate about actors’ safety, and this was a huge need in the industry.”

While scenes of intimacy are never real, Matarelli Carlson says directors must keep in mind that actors’ brains and bodies respond differently than in other scenes, such as fights.

“We know fundamentally that we’re not really mad at each other, and it is so technical and so precise, I never worry that I’m going to accidentally get really mad one time and stab my partner. But it’s much blurrier when it comes to intimacy, because you are really hugging that person. You are really kissing that person,” Matarelli Carlson said. “Our bodies are wired to respond to that kind of intimacy, so it becomes much blurrier for actors when it comes to intimacy. Endorphins start firing and things like that in the body, so you come away from that scene thinking ‘wait, am I in love with that person?’”

Matarelli Carlson says intimacy directors can emphasize boundaries and implement closure exercises to help actors step out of the scene, and cope with confusing emotions.

One common misconception is that intimacy coordinators and directors are “censoring” or “sanitizing” the material they work with. However, Matarelli Carlson says that when actors are supported and taken care of, they are able to craft scenes that “sizzle.” “In no way are we there to censor anything, or sanitize the work. We just want to make sure that everybody is 100 percent enthusiastically committing to [the story] being told,” Matarelli Carlson said. “Often based on [intimacy] work, the work gets deeper, it gets more committed, and because actors feel more supported they feel more confident getting into something that really does deepen the story.”

While not all universities or theatre companies have an intimacy director in-house, Matarelli Carlson says that intimacy workshops through Intimacy Directors and Coordinators (IDC) can help protect the actors, educate students and educators about this emerging field, and send them out into the field with knowledge that will help them avoid being taken advantage of. In practice, directors can emphasize communication and boundaries, and make sure actors know what the roles entail at auditions. Actors can then feel empowered to decline roles that they aren’t comfortable with. “If it’s a story the actor is not comfortable telling, I think they should be allowed to decline those things up front,” Matarelli Carlson said.

Unfortunately, the “trendy” nature of the position has led to some directors and choreographers calling themselves intimacy directors or coordinators without having qualifications or the proper mental health training. Matarelli Carlson says this is dangerous for the industry and for the actors. “You can really injure people mentally and emotionally if you’re doing it incorrectly or if you’re doing it irresponsibly,” Matarelli Carlson said.

For more information about intimacy directors, coordinators, training and workshops, visit https://www.idcprofessionals.com/ or https://www.teamidi.org/

Graphic: Shaniah Garrick/ The Johnsonian