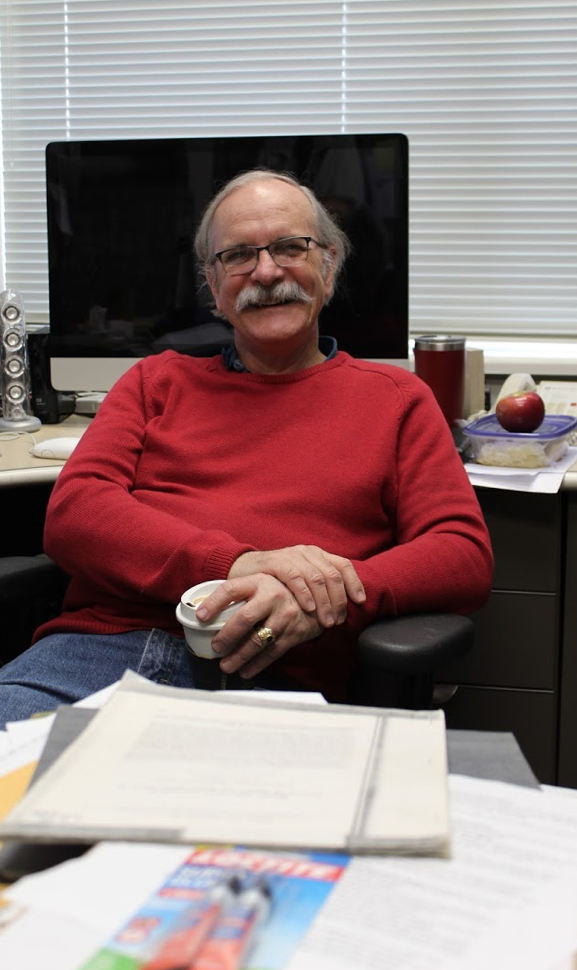

Julian Smith, professor of biology, received the Distinguished Research Leadership Award from the South Carolina Governor’s School for Science and Mathematics

Smith humbly accepted the award. He said he was “surprised and pleased” to have received it.

“I don’t think about it as something special that I do. It’s just a continuation of what I normally do,” Smith said.

Smith is a mentor for rising seniors at the Governor’s School. Students complete an independent research project during the summer. Smith’s role is to help design and carry out the projects. Two of his students went on to publish their findings.

“It’s sort of lucky when that happens because the student has just a summer to come completely up to speed on the literature. In many cases, they’ve never read primary literature before. Then, the student has to want to publish it badly enough to continue doing a lot of writing on through the end,” Smith said.

A love for helping students understand complex concepts is what led Smith to become a mentor for the Governor’s School.

“It’s just a lot of fun to watch the light of realization come on, to watch the people’s ‘aha’ moments, to have them be able to look back on all the stuff that they’ve been able to do. It’s just a blast,” Smith said.

Though he would like to continue in the mentoring program, his wife made him promise to stop working weekends once he turns 70 years old.

“I probably want to retire sometime around the time I’m 70. I’m 65 now, and my wife’s made me promise to quit working Saturdays and Sundays when I’m 70, so we’ll see. I’ll continue mentoring students in the future, absolutely,” Smith said.

Smith’s research focuses on meiofauna, or the microorganisms found between grains of sand.

“Go to the beach, pick up a handful of sand. You’re holding about 2,000 animals. Where the waves are breaking, they’re pretty dense right there. More than 50 percent of them don’t have formal scientific names at this point,” Smith said.

Specifically, he studies the evolution of certain structures in these organisms, such as an “anterior pincer-like proboscis” and venom glands.

Smith and a few colleagues are researching the effects of beach nourishment, the replacement of sand on eroded shores, has on these meiofauna.

“We just got our first samples back comparing a nourished beach to an unnourished beach. It turns out that the community diversity is higher in the nourished beach. That’s not what we expected, but in hindsight having a wide variety of different grains of sand shape and sizes, which is what nourishment does, it makes the beach more coarse, you get a lot of shell hash left in there, probably provides more microhabitats for the animals. So whether it’s a good thing or a bad thing, we don’t know yet, but we do know it does change it,” Smith said.

Smith credits his godmother as one of his biggest inspirations that got him into the scientific field. A cardiothoracic surgeon born in 1921, she was the only woman in her class at medical school.

“Back then, fewer than two percent of women medical residents went into surgery. From the time I was about five or six, for about 10 years she drove up from Augusta, Georgia grabbed me every summer and drove me into the Smithsonian. She had a huge influence on me. She helped me buy my first microscope when I was in middle school. That meant a lot to me,” Smith said.

This microscope is still proudly displayed in his office, among various equipment and pictures of family.

Aside from mentoring budding scientists, Smith can be found designing buildings in his free time. He was the chair of the building committee for Dalton Hall in 1999, a fond memory.

“I’m glad I’ll never have to do that again,” Smith said.

Because the architect, who was in charge of laying out cabinets and shelves, quit in the middle of the project, Smith took it upon himself to finish the job.

“I taught myself the architectural CAD program. Installed it on my own computer and spent about five weeks putting all the casework in the labs where it was supposed to go. Then having the architect print out the blueprints. It was fun to do. I’m kind of techy, mechanical, but I’m glad that’s over because it was kind of horrible. I couldn’t do anything else for, like, five weeks,” Smith said.

In his 33 years at Winthrop, Smith is pleased with the way that the research atmosphere has shifted in his time at the school.

“The research atmosphere here has changed enormously in that time. I spent the first five years or so buying used equipment at state surplus or building the equipment that I needed. We just spent half a million dollars on brand new equipment,” Smith said.

Perhaps the most important characteristics Smith possesses are his passion for research and science and his dedication to the job.

“I just get a real kick out of understanding stuff and then explaining that to people. The other thing about being a scientist is, especially in my field, is 100 percent of the time you get to see stuff that no one has seen before, to discover something new. That just keeps me going. I would do this if no one paid me,” Smith said.